Targeted therapies in the new era of molecular medicine are currently used in most oncologic settings with increasing success. They have hit the prime time and are the star agents for many oncologic diseases. Yet, they add an additional layer of complexity to cancer care. They represent a paradigmatic shift in treatment based on specific gene expression or mutational analysis. This deepening understanding of biology has led to overall survival and symptom-based improvements. However, biological “personalization” is often translated into the general term “personalized medicine,” which has traditionally been used broadly to mean patient-centered care, the biopsychosocial model that conceptualizes illness within the context of a patient’s total life situation. This perspective emphasizes the importance of interactions between biological, psychological, and social factors in the context of disease and treatment. Ironically, very little is known about these issues in molecular-based medicine.

How Do Patients Understand Treatments That Are Based on the DNA of Their Tumor? What Are the Psychological Considerations That Arise for Patients?

The patient experience with targeted therapies is not well documented in the literature. This contrasts with the burst of psychological studies and remarkable number of citations that became available after the advent of genetic testing for heritable tumors, such as BRCA1/2 in breast and ovarian cancer in healthy patients (for reviews, see references 2 and 3). The experience more closely parallels that of patients receiving traditional chemotherapy treatment. Similarities exist between informed consent for chemotherapy, clinical trials, and targeted therapies. As such, clinical experience suggests that patients are less concerned about the molecular basis of treatment and more concerned about efficacy and side effects. Patients’ expectations for the success of targeted therapies appear to be similar to the experience with chemotherapy in that their hope for efficacy far exceeds the actual survival data.4,5

In this transitional era from cytotoxic to targeted therapy, it is incumbent upon the oncology community to examine psychological and social implications of targeted therapy in order to provide an approach to patient-centered care with an eye toward improving quality. However, research at the intersection of oncology and mental health comprises a total of only 0.26% of all oncology publications and 0.51% of all mental health publications over the past 10 years.6 Treatment decisions need to be guided by scientific and technological advances, but also by aspects of the patient’s personal experience. A qualitative study of patients with metastatic lung, breast, and colorectal cancer found that patients did not understand somatic genetic testing and were not aware of or harbored misunderstandings about the term “personalized medicine.”7 If we want to advocate for “patient-centered care” in oncology, we must do more than simply call it “personalized.”8 In order to provide a foundation for future work at this intersection, this paper reviews the current literature on psychological and social issues associated with targeted therapies and their impact on clinical care and research.

Materials and Methods

Databases Included in the Search

Literature searches were conducted utilizing PubMed on April 6 and April 24, 2014, and Web of Science (WOS) on April 26, 2014.

Search Strategy

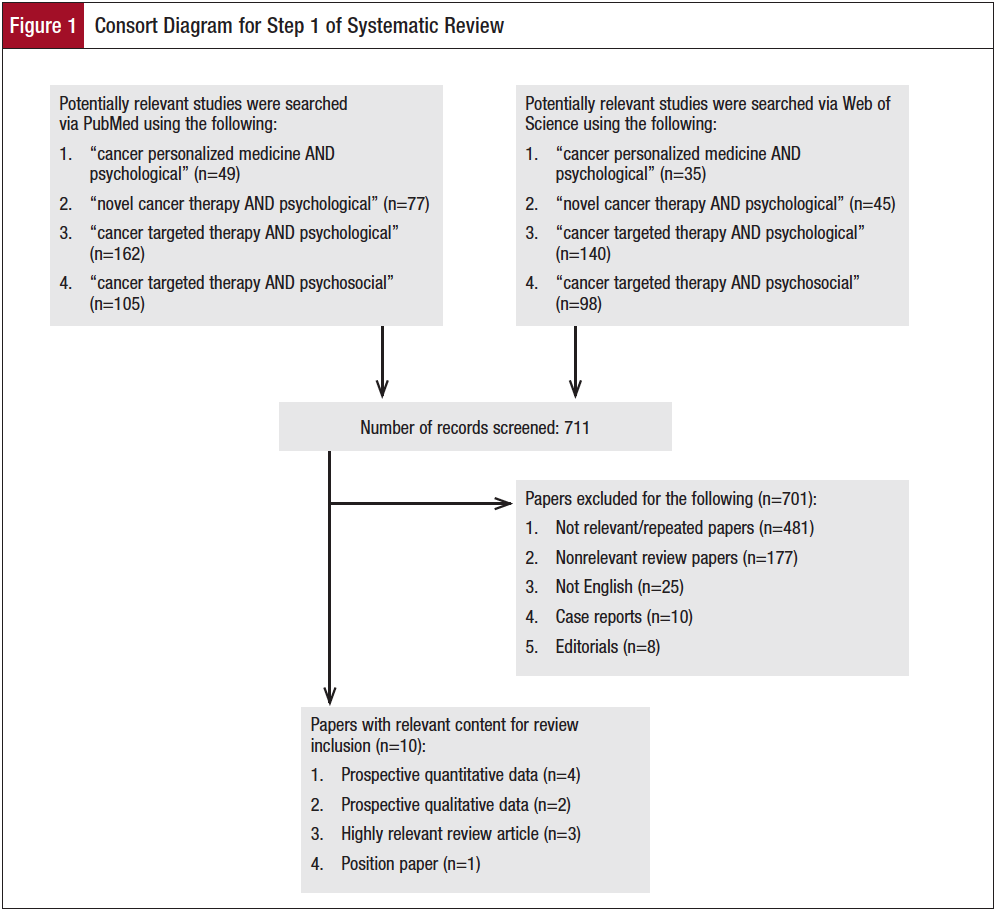

This review was performed in 2 parts and tracked publications back to 1995. Step 1 utilized a free-text key term search, and step 2 combined the key search terms (see below) with specific targeted therapy drugs as defined by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). For step 1, free-text terms were entered in both PubMed and WOS to search for citations containing the following: “cancer personalized medicine AND psychological,” “novel cancer therapy AND psychological,” “cancer targeted therapy AND psychological,” and “cancer targeted therapy AND psychosocial.” For step 2, a search was conducted in PubMed only using the terms “psychological” and “quality of life” in combination with each targeted cancer therapy as designated by the NCI (total 39 drugs) as listed on www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Therapy/targeted on April 24, 2014. This review adhered to the guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis report.

Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria in step 1 were more broadly inclusive and accepted relevant review papers as well as prospective or retrospective studies that were either qualitative or quantitative. In step 2 (ie, review of specific targeted agents), the inclusion criteria were restricted to studies that reported prospectively obtained quantitative data (ie, no review papers) in which quality of life (QOL) was either the primary or secondary aim and QOL scales specifically included psychological content. All included articles were peer reviewed, involved human research, were written in English, and involved psychological or QOL content. Exclusion criteria included review articles (for step 2 only), editorials, and preclinical studies.

Screening and Data Abstraction

Article titles and abstracts were reviewed for psychological content. Articles were included if they related to targeted therapy (based on molecular/cellular targets used in cancer treatment) and addressed a psychological issue. Steps 1 and 2 of the literature search were conducted by DCM. Inclusion of “relevant” articles was decided by DCM according to the topic relevance, article quality, and data analysis methodology. Inclusion of relevant articles was reviewed by JGH, and disagreements settled by author discussion.

Results

Step 1 identified 711 relevant citations using PubMed and WOS (Figure 1), of which only 10 were found to be relevant (Table 1). Three studies evaluated patients’ perception of personalized medicine7,9,10; 4 studies reported symptoms related to targeted therapy11-14; 2 position papers called for greater patient-centered care15,16; and 1 paper reviewed oral chemotherapy management.17 Specifically, the 2 position papers called for improved communication in advanced cancer15 and enhanced use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in clinical care.16 Among the themes reported were the lack of patient understanding and awareness of the term “personalized medicine”7; patient questions related to the term “personalized”9; and doctor-patient communication challenges regarding novel therapeutics in presentations of molecularly based therapy.10 Additional citations addressed side effects associated with targeted therapies such as psychological distress,11 depression,12,13 and sexual dysfunction.14 One study reviewed the management of oral chemotherapy and its

challenges.1

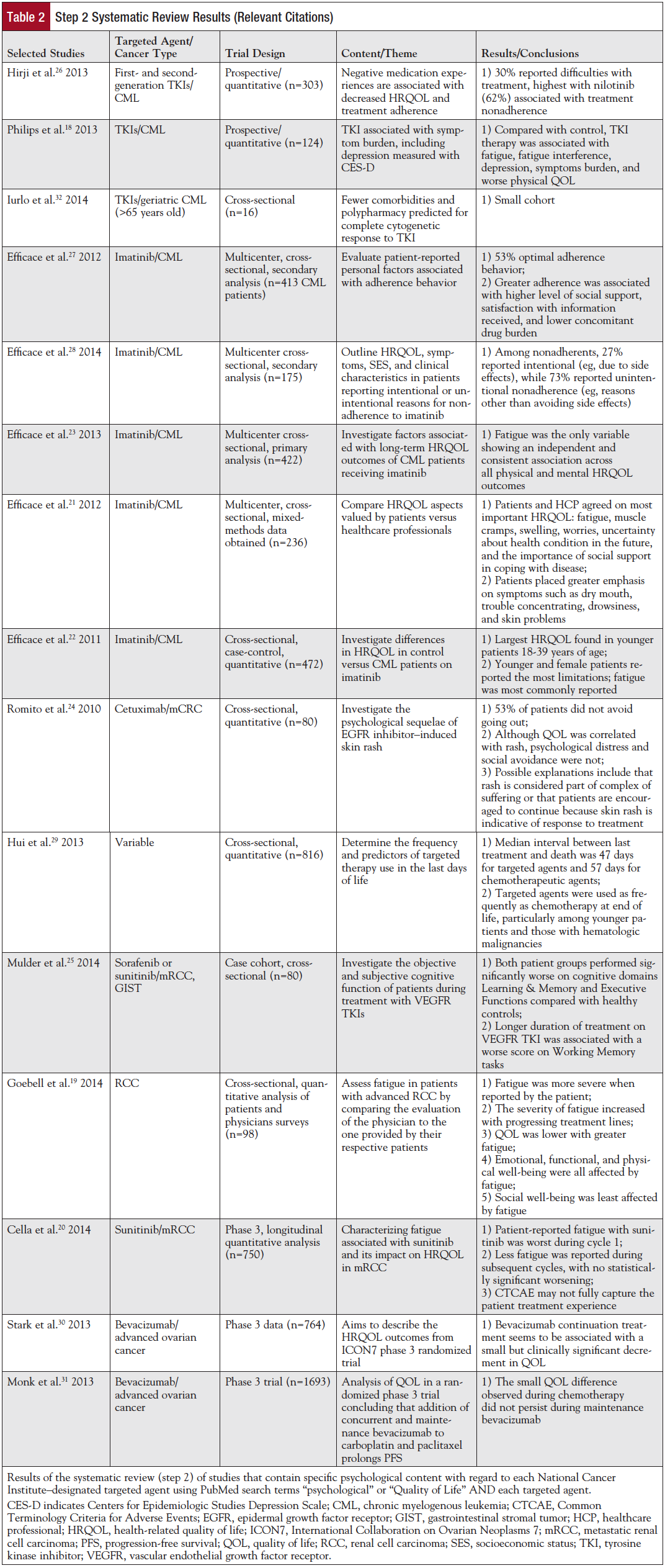

Step 2 identified 75 citations related to “psychological” and 2262 citations related to “quality of life.” The vast majority of studies addressed QOL and showed either a benefit in QOL from the therapy or that QOL was noninferior to other treatments. Fifteen papers were deemed relevant to this review (Table 2). More publications were identified for drugs that have been FDA approved for a longer period of time (Figure 2). Publications related to QOL or psychological considerations generally lagged behind FDA approval by 5 to 8 years.

The psychological themes from the 75 citations in step 2 studies are presented in Table 2. Eleven of 15 selected papers dealt specifically with a symptom (eg, depression,18 fatigue,19-23 rash,24 cognitive function25), or adherence26-28 to a regimen of targeted therapy (eg, imatinib, sunitinib, cetuximab). One paper evaluated targeted therapy use at the end of life.29 Most of the QOL trials only evaluated tolerability and did not explore other experiential or psychological issues. Of the QOL trials that used an instrument with psychological measures and were included in the study, all showed favorable tolerability except for a small decrement of QOL with bevacizumab in ovarian cancer.30,31 Six of the 15 studies evaluated imatinib in the setting of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with an emphasis on adherence.22,23,26-28,32 Common reasons for stopping imatinib were negative medication experiences,26 polypharmacy in patients on many medications,32 and low social support or lack of satisfaction with medication information.27 Patient-level differences were noted in intentional versus nonintentional nonadherence: younger age, lower socioeconomic status, and poorer understanding of treatment rationale.28 Symptom burden of imatinib in CML was fatigue, depression, and reduced QOL while on treatment.18,23 Healthcare professionals often underestimated the severity of such patient-reported symptoms.21

Discussion

This review of extant literature revealed a paucity of studies that explored psychological or social aspects of targeted therapies, perhaps with the exception of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and fatigue. However, several points become clear from those studies reported in this review. First, the term “personalized medicine” is poorly understood by patients. They do not relate molecular medicine to personalization, which is also consistent with the experience of the authors. “Precision medicine” or targeted therapy may be preferable terms. This also reduces the confusion with the widespread use of terms like “patient-centered care” to denote attention to the whole patient, from biology through psychological and social issues.

Second, although few studies examined this issue, the review did not find evidence that cancer patients have concerns about genetic testing of their tumor to inform targeted treatment. This is in sharp contrast to the careful preparation of healthy individuals undergoing genetic testing for hereditary cancer syndromes where genetic counselors are often involved.2,3 In fact, patients readily expressed that they did not understand the described “pathways” but that side effects and treatment outcome were much more important in giving consent.7,12 This suggests that patients’ motivations and concerns regarding targeted therapeutics appear to be similar to those observed in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy. For example, in a CALGB study, patients were asked why they agreed to receive chemotherapy for a wide range of cancers.33 Patients were clear that they feared the outcome of the cancer if they did nothing. They hoped for a favorable benefit and they trusted the oncologist. This triad of fear, hope, and trust appears highly relevant to patients receiving new therapies today. Extended description of the complex molecular drivers and biologic mechanisms may not be essential or indeed desired except by those patients who request detailed explanations in order to make an informed treatment choice. It must be noted, however, that as genomic sequencing of tumors increases, the potential for patients to learn meaningful, incidental germline risk information also increases. Genetic incidentalomas will become more prevalent and demand further attention into their ethical, clinical, and psychological implications.34

Similar to the advent of chemotherapy a few decades ago, the oncologic community and the public at large are both excited by the new hope that novel therapies bring. News from national cancer meetings is widely reported with great enthusiasm, and there is an exuberant sense that a new era of cancer care has arrived.35,36 For newly diagnosed patients, the wait for a molecular analysis is anxiety-provoking and is colored by “Will I qualify? Do I have the right gene?” Having the gene is viewed as winning the lottery, and not having it is often perceived with sadness, as if it were a personal failure. Both the oncologist and the patient share the optimism of a new treatment.

However, for the patient with advanced disease, it is necessary to present the targeted therapeutic treatment with hope, but also tempering it with reality. Data are clear that patients’ expectations of outcome in receiving phase 1 clinical trial therapy far exceed the reality.37 This issue in communication can be most difficult in the advanced cancer setting after multiple lines of therapy have been used. A new drug is a symbol of hope that is powerful; however, it may serve as a deterrent from dealing with the realities of disease burden. Even so, moving on to the next agent may actually symbolize defeat in the mind of the patient. Caring and commitment inspire hope and trust for the patient who understands, “I am cared for.” These responses help to mitigate targeted therapy overuse at the end of life. Physicians and care teams play an enormous role in the lives of patients who are coming to terms with mortality. This constancy and concern is therapeutic in itself.

This review found that all targeted therapies had reports of their impact on QOL (functioning in health-related domains). Overall, targeted therapies are well tolerated, with fatigue and rash being the most commonly reported symptoms. Depression, anxiety, and cognitive dysfunction are reported with specific therapies and will need to be explored further. Adherence to oral therapies, late-emerging side effects, and psychological ramifications will become increasingly important as oral targeted agents depend on patient administration and are generally utilized for longer periods. The oncologist has an obligation to arrive at a decision that is truly shared with a patient who understands the treatment plan, goals, and side effects and that considers the patient’s personal values and preferences. To that end, shared decision making should consider the financial burden of treatment as well.38

In terms of future research, clinical trials of targeted therapies increasingly utilize PROs, which far more adequately capture subjective symptoms and increase patient satisfaction and sense of participation.39 Symptoms are often underestimated by oncologists’ reported observations.39 The FDA definition of a PRO is “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.”39 In clinical care, collecting and providing PRO results to oncologists have been shown to have positive effects on patient-physician communication.40 These discussions were raised primarily by patients or their relatives; however, this suggests that the proper utilization and interpretation of PRO data need to be explored further. PROs could be used to further understanding and knowledge of the informed consent process for targeted therapies. Compared with the rich literature on informed consent for chemotherapy and clinical trials, there is currently very little information regarding the optimization of informed consent in the era of precision medicine. This trend in utilizing PROs should continue as new therapies emerge and side effects can be identified and anticipated.

Limitations of this review include the likelihood that limited search terms may not have captured all potentially relevant topics, and that only English language studies were reviewed. An additional limitation is that the review did not include studies of the financial burden of expensive targeted drugs, although such burden may add to psychological stress. For instance, “financial toxicity” was reported in 42% of an insured cohort of 254 patients who had been prescribed a targeted treatment. They described applying for copayment assistance (75%), reducing spending on food (46%), taking less than prescribed (20%), and partially filling (19%) and avoiding filling prescriptions altogether (24%).38 Leaders in the oncology community have recently engaged in the economic aspects of rising drug costs for patients.41

In summary, this review confirms that psychosocial research has not kept pace with rapid scientific advances in targeted therapies. Although patients may receive detailed information about the more complex basis upon which their treatment is determined, there is currently little research evidence available to help oncologists educate their patients on the broader psychosocial implications of their therapies. The new psychological concerns expressed by patients receiving targeted therapies appear to be most similar to those concerns observed in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy and relate to questions about side effects and outcomes. Patients need adequate biological and molecular information about the treatment proposed, but on the whole, information on the clinical outcome and side effects is far more important to them. Existing research suggests that fatigue and rash are the most commonly observed symptoms so far with targeted therapies and that QOL remains tolerable. Specific subjective symptoms, particularly psychological, will need further study with each new agent. In general, patients accept experimental treatments because they hope for a better outcome, fear the disease without treatment, and trust the doctor’s recommendation for treatment. Research into the patient experience with targeted therapy should inform shared decision making and clinical care in this era of genome-driven treatment. Psychological aspects of targeted therapies are beginning to receive attention, yet much work remains to be done to assure that truly patient-centered care remains the goal in the era of targeted therapies.

References

- Holland JC, Rowland JH, eds. Handbook of Psychooncology: Psychological Care of the Patient with Cancer. Volume 236. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1989.

- Hamilton JG, Lobel M, Moyer A. Emotional distress following genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 2009;28:510-518.

- Heshka JT, Palleschi C, Howley H, et al. A systematic review of perceived risks, psychological and behavioral impacts of genetic testing. Genet Med. 2008;10:19-32.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733-742.

- Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381-390.

- Purushotham A, Bains S, Lewison G, et al. Cancer and mental health – a clinical and research unmet need. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2274-2278.

- Gray SW, Hicks-Courant K, Lathan CS, et al. Attitudes of patients with cancer about personalized medicine and somatic genetic testing. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:329-335.

- Oliver A, Greenberg CC. Measuring outcomes in oncology treatment: the importance of patient-centered outcomes. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:17-25.

- Cornetta K, Brown CG. Balancing personalized medicine and personalized care. Acad Med. 2013;88:309-313.

- Thorne SE, Oliffe JL, Oglov V, et al. Communication challenges for chronic metastatic cancer in an era of novel therapeutics. Qual Health Res. 2013;23:863-875.

- Shun SC, Chen CH, Sheu JC, et al. Quality of life and its associated factors in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving one course of transarterial chemoembolization treatment: a longitudinal study. Oncologist. 2012;17:732-739.

- Capuron L, Ravaud A, Miller AH, et al. Baseline mood and psychosocial characteristics of patients developing depressive symptoms during interleukin-2 and/or interferon-alpha cancer therapy. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18:205-213.

- Van Gool AR, Kruit WH, Engels FK, et al. Neuropsychiatric side effects of interferon-alfa therapy. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25:11-20.

- Rouanne M, Massard C, Hollebecque A, et al. Evaluation of sexuality, health-

related quality-of-life and depression in advanced cancer patients: a prospective study in a phase 1 clinical trial unit of predominantly targeted anticancer drugs. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:431-438.

- Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:755-760.

- Garcia SF, Cella D, Clauser SB, et al. Standardizing patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer clinical trials: a patient-reported outcomes measurement information system initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5106-5112.

- Viele CS. Managing oral chemotherapy: the healthcare practitioner’s role. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:S25-S32.

- Philips KM, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Sotomayor E, et al. Quality of life outcomes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a controlled comparison. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1097-1103.

- Goebell PJ, Münch A, Müller L, et al. A cross-sectional investigation of fatigue in advanced renal cell carcinoma treatment: results from the FAMOUS study. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:362-370.

- Cella D, Davis MP, Négrier S, et al. Characterizing fatigue associated with sunitinib and its impact on health-related quality of life in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2014;120:1871-1880.

- Efficace F, Breccia M, Saussele S, et al. Which health-related quality of life aspects are important to patients with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving targeted therapies and to health care professionals? GIMEMA and EORTC Quality of Life Group. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1371-1381.

- Efficace F, Baccarani M, Breccia M, et al. Health-related quality of life in chronic myeloid leukemia patients receiving long-term therapy with imatinib compared with the general population. Blood. 2011;118:4554-4560.

- Efficace F, Baccarani M, Breccia M, et al. Chronic fatigue is the most important factor limiting health-related quality of life of chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib. Leukemia. 2013;27:1511-1519.

- Romito F, Giuliani F, Cormio C, et al. Psychological effects of cetuximab-induced cutaneous rash in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:329-334.

- Mulder SF, Bertens D, Desar IM, et al. Impairment of cognitive functioning during sunitinib or sorafenib treatment in cancer patients: a cross sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:219.

- Hirji I, Gupta S, Goren A, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML): association of treatment satisfaction, negative medication experience and treatment restrictions with health outcomes, from the patient’s perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:167.

- Efficace F, Baccarani M, Rosti G, et al. Investigating factors associated with adherence behaviour in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: an observational patient-centered outcome study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:904-909.

- Efficace F, Rosti G, Cottone F, et al. Profiling chronic myeloid leukemia patients reporting intentional and unintentional non-adherence to lifelong therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Leuk Res. 2014;38:294-298.

- Hui D, Karuturi MS, Tanco KC, et al. Targeted agent use in cancer patients at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:1-8.

- Stark D, Nankivell M, Pujade-Lauraine E, et al. Standard chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in advanced ovarian cancer: quality-of-life outcomes from the International Collaboration on Ovarian Neoplasms (ICON7) phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:236-243.

- Monk BJ, Huang HQ, Burger RA, et al. Patient reported outcomes of a randomized placebo-controlled trial of bevacizumab in the front-line treatment of ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128:573-578.

- Iurlo A, Ubertis A, Artuso S, et al. Comorbidities and polypharmacy impact on complete cytogenetic response in chronic myeloid leukemia elderly patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:63-66.

- Penman DT, Holland JC, Bahna GF, et al. Informed consent for investigational chemotherapy: patients’ and physicians’ perceptions. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:849-855.

- Bombard Y, Robson M, Offit K. Revealing the incidentalome when targeting the tumor genome. JAMA. 2013;310:795-796.

- The New York Times. Targeted cancer. http://topics.nytimes.com/top/news/health/series/target_cancer/index.html. Accessed September 26, 2014.

- The Washington Post. New therapies raise hope for a breakthrough in tackling cancer. www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/new-therapies-raise-hope-for-a-breakthrough-in-tackling-cancer/2014/02/14/b4f8e4fc-8dad-11e3-95dd-36ff657a4dae_story.html. Accessed September 26, 2014.

- Jenkins VA, Anderson JL, Fallowfield LJ. Communication and informed consent in phase 1 trials: a review of the literature from January 2005 to July 2009. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1115-1121.

- Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381-390.

- Basch E, Abernethy AP, Mullins CD, et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4249-4255.

- Takeuchi EE, Keding A, Awad N, et al. Impact of patient-reported outcomes in oncology: a longitudinal analysis of patient-physician communication. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2910-2917.

- Kantarjian HM, Fojo T, Mathisen M, et al. Cancer drugs in the United States: Justum Pretium – the just price. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3600-3604.