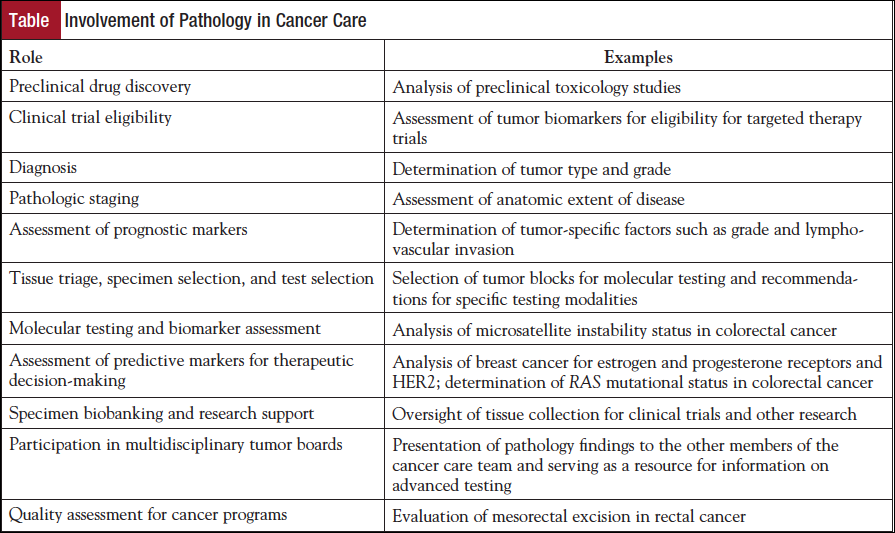

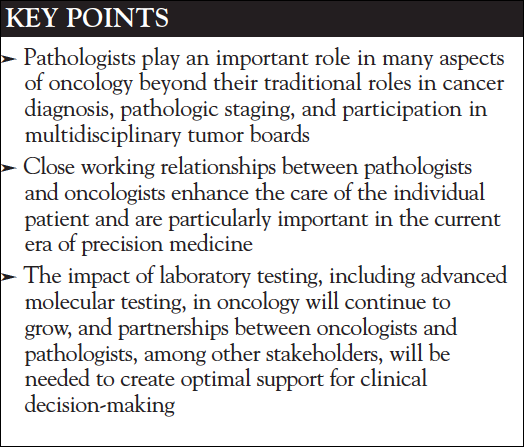

Pathologists have traditionally been most visible to the other members of the cancer care team in their roles in cancer diagnosis, pathologic staging, and as an integral member of the multidisciplinary tumor board. However, in the era of personalized medicine, the responsibility of the pathologist is expanding to include preclinical drug testing, assessment of prognostic markers, triage of tissue for molecular testing and consultation on the feasibility of such testing, companion biomarkers and diagnostics, and biobanking of samples for future clinical testing and research (Table). In addition, the pathologist may play a role in determination of clinical trial eligibility, based on pathologic findings and molecular test results, and assessment of the quality of clinical care (eg, number of lymph nodes retrieved and completeness of mesorectal excision in colorectal cancer resections). Given these myriad activities, it is not surprising that a large part of the pathologist’s working day is spent on oncology-related clinical care activities; in the Canadian system, it has been documented that two-thirds of anatomic pathologists’ time is spent in oncology-related activities in cytopathology and surgical pathology.1

Pathologists have traditionally been most visible to the other members of the cancer care team in their roles in cancer diagnosis, pathologic staging, and as an integral member of the multidisciplinary tumor board. However, in the era of personalized medicine, the responsibility of the pathologist is expanding to include preclinical drug testing, assessment of prognostic markers, triage of tissue for molecular testing and consultation on the feasibility of such testing, companion biomarkers and diagnostics, and biobanking of samples for future clinical testing and research (Table). In addition, the pathologist may play a role in determination of clinical trial eligibility, based on pathologic findings and molecular test results, and assessment of the quality of clinical care (eg, number of lymph nodes retrieved and completeness of mesorectal excision in colorectal cancer resections). Given these myriad activities, it is not surprising that a large part of the pathologist’s working day is spent on oncology-related clinical care activities; in the Canadian system, it has been documented that two-thirds of anatomic pathologists’ time is spent in oncology-related activities in cytopathology and surgical pathology.1

The effective multidisciplinary tumor board nearly always includes at least 1 pathologist. In the past, the role of the pathologist has been primarily to present anatomic pathology findings, such as cytology specimens, biopsies, and resections. Presentation of the pathologic staging at tumor boards has been a particularly important role. The foundational contributions of the pathologists in this regard have not been lessened, but pathologists are increasingly playing an important supporting role in determination of treatment recommendations by providing expert consultation on use and interpretation of advanced molecular testing.

Increasing demands on pathologists’ time spent in cancer-related activities is compounded by a potential shortage of pathologists, partly due to retirement of a graying workforce and an insufficient number of new practitioners entering the system. A gap of 5700 in the pathologist workforce between supply available and numbers needed has been projected for the United States for 2030,2 with similar concerns about a decreasing supply of pathologists in Canada relative to cancer-related demands for pathology services.3

Diagnosis

The diagnostic tool kit used by pathologists has expanded exponentially with the advent of personalized oncology. Ancillary studies such as immunohistochemistry and molecular testing are often used as prognostic and predictive markers, but their application to diagnosis should not be overlooked. For instance, in hematopoietic and lymphoid malignancies, subdivisions of most disease categories are defined by molecular classification, with emerging platforms based on NanoString technologies and integrated fluidic circuit technology considered superior to immunohistochemistry. Similarly, diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors is based not just on histologic appearance but is confirmed by demonstrating expression of KIT (CD117) and/or DOG1, or PDGFRA mutation in rare cases if these markers are negative. Cytogenetic features have proven particularly useful in diagnosis of sarcomas: approximately 95% of cases of myxoid liposarcoma demonstrate the FUS-DDIT3 chimeric gene due to reciprocal t(12;16)(q13;p11),4 aiding in distinction from other myxoid tumors. Molecular testing is also useful in discriminating between lipoma and atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma.4 These refinements in diagnosis based on improved understanding of disease pathobiology represent important advances in determining optimal therapy for many types of cancers.

Assignment of Pathologic Stage

Assessment of extent of disease remains a foundational element in driving clinical decision-making in oncology for the individual patient. Determination of pathologic stage is also necessary to evaluate results of treatments and clinical trials, as well as facilitating population science by enabling exchange in comparison with information between cancer-specific registries.5 In addition to applying various staging systems, pathologists are key participants in revision and refinement of these systems. Each disease site–specific expert panel for the revision of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual included at least 1 anatomic pathologist, and many included a molecular pathologist. As an example of pathology-led input, changes to the staging system for pancreatic carcinoma in the AJCC 8th edition6 were initiated by pathologists, who noted ambiguities inherent in determination of extrapancreatic extension.7

Review of pathologic and clinical staging is an important activity in multidisciplinary tumor boards and is one of the most commonly discussed items of most tumor boards.8 Inadequate pathology information has been specifically identified as a barrier to reaching a clinical decision.9 In addition to a physical presence at a traditional tumor board, pathologists play an important role in so-called virtual tumor boards, which meet via electronic means. Although virtual tumor boards are a relatively recent development, they may offer advantages by increasing access of oncologists in the community to subspecialty pathology experts. Molecular tumor boards provide a forum in many institutions to educate and disseminate information on relevant clinical trials and interpretation and application of genetic data.10 Regardless of format, positive outcomes for all types of tumor boards depend on availability of qualified and effective faculty in all disciplines.11

Assessment of Prognostic Markers

The AJCC has expanded the use of biomarkers and nonanatomic prognostic factors in the 8th edition of the Cancer Staging Manual, with the goal of remaining relevant to clinical care in the era of personalized medicine.6 Many of these site-specific factors, which in some disease sites are incorporated into assigning stage groupings, are histopathologic features of the particular tumor type, such as histologic grade group for prostate cancer, histologic type for thyroid cancer, and mitotic index for melanoma, and thus fall under the domain of the surgical pathology. Others, such as prostate-specific antigen serum levels and serum markers for testicular cancer, are based in the clinical laboratory.6 As the incorporation of these nonanatomic factors into staging and clinical decision-making for individual patients becomes more important, the role of the pathologist correspondingly increases in assessment of disease extent and prognosis.

Molecular Testing and Biomarker Assessment

Although pathologists have been called the “gatekeepers” for access to molecular testing,12 a more inclusive approach involves pathologists educating oncology colleagues regarding appropriate test utilization as part of a multidisciplinary team approach.13

Coordination of molecular testing involves the referring physician, the pathologists, and the laboratory. The timing of testing is generally the choice of the treating oncologist and varies among practice settings and tumor type, but it is ideally determined by consensus between the pathologists and oncologists. For instance, whereas assessment of the HER2 expression or amplification and expression of the estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor is routinely performed as a reflex test on the diagnostic biopsy for breast cancer to facilitate treatment planning, HER2 testing in gastric cancer may be delayed until it is confirmed that the patient has locally advanced or metastatic disease and is a candidate for combination chemotherapy that includes a HER2-targeted agent. Test ordering procedures and criteria for reflex testing, in the absence of evidence-based guidelines, should be developed with input from all stakeholders, most commonly the medical oncologists and pathologists, and balance timeliness with need.

As drugs move from clinical trials into practice, clear guidance to both cancer care providers and pathologists is needed regarding which patients to test, when to implement testing, and how to perform and interpret the tests. Evidence-based guidelines such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guidelines on HER2,14 estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor15 testing in breast cancer have helped to standardize these tests across clinical laboratories and provide guidance on specimen handling, test methodology and validation, interpretation of immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization, and proficiency testing for routine clinical practice. This level of standardization is necessary for the rigorous quality assurance needed for both technical and interpretative aspects of biomarkers that determine eligibility for specific targeted therapies, which are often costly and likely to be ineffective in the wrong patient population. Such evidence-based guidelines are developed most effectively through a partnership in a multidisciplinary environment with input from medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists and pathologists and other stakeholders.

Pathologists play an important role in optimizing the practical implementation of biomarkers and in educating their oncologist colleagues. Often this education is case-based and occurs in the setting of multidisciplinary tumor boards where pathologists have the opportunity to recommend advanced testing, including molecular testing, in the context of the available clinical information. These interactions and educational opportunities are multidimensional, and although the pathologist is advisory to the other members of the cancer care team in this capacity, he or she mutually benefits from the discussion about how these test results are interpreted and their impact on clinical decision-making. Without effective interactions with colleagues from other disciplines, pathologists may be viewed as too exacting and rigid regarding detailed requirements for testing.13 In one institution, creating a multidisciplinary team for colorectal cancer care resulted in a significant increase in advanced pathology testing (29.6% vs 10.6%) and adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, highlighting the benefits of the multidisciplinary approach.16

Lack of clear guidelines for clinical indications for ordering molecular testing has been cited as an important barrier to testing in a survey of physicians providing cancer care in Ontario.17 Although 46% of physicians in this study were confident in their ability to assess whether molecular oncology testing was indicated, only 34% were confident that they knew which test to order. These findings highlight the need for pathologists and other laboratory professionals to guide and educate treating physicians in the appropriate usage of advanced molecular testing in the care of cancer patients and emphasize the importance of the pathologist as a resource for clinicians.

Tissue Triage and Test Selection

An important and often overlooked role of the pathologist is to prioritize testing of small tumor samples. In most cases, the available tissue is formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks. At the time of the initial biopsy, however, tissue may be allocated for specialized testing such as flow cytometry if a lymphoid neoplasm is suspected, or fresh or frozen tissue set aside for molecular testing panels requiring such tissues. Fortunately, most commercial gene signature panels, even those originally developed with fresh or frozen tissue such as MammaPrint,18 can be performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue, obviating the need for obtaining additional fresh tissue after an initial diagnostic biopsy if the sample is large enough. However, whole genome sequencing on tumors is more easily performed on frozen rather than fixed tissue, as freezing avoids the problem of DNA cross-linking that occurs with formalin fixation. In addition, identification of epigenetic changes often requires fresh or frozen tissue. Sequencing of cell-free DNA from plasma may in the future represent an approach to tumor genomic profiling that eliminates the need for larger specimens and special tissue handling and overcomes the problem of tumor heterogeneity,19 but current practice relies on careful husbandry of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue by the pathologist for most studies.

Even prior to definitive diagnosis, tissue can be conserved if appropriate clinical information is provided to the pathologist. For instance, if the pathology requisition includes the information that a liver biopsy is performed for diagnosis of a mass lesion rather than medical liver disease, routine special stains such as Masson trichrome for fibrosis and iron stain are often not performed to conserve tissue for additional tumor-specific testing if needed. Obviously, close communication between the pathologist and the treating clinicians is necessary for optimal use of tissue and care of the cancer patient.

The pathologist is also well poised to recommend specific tests when more than 1 methodology is available. For instance, colorectal cancers may be tested for microsatellite instability by polymerase chain–based reaction or mismatch repair protein deficiency by immunohistochemistry, for evaluation for Lynch syndrome, and as a prognostic and predictive marker that may influence treatment decisions. Each method of testing has advantages and drawbacks.

Companion diagnostic assays used to select cancer patients for treatment with targeted therapies pose special problems in pathology, requiring rigor in development and clinical validation.20 While the historical approach of regulatory approval in the United States has been 1 assay-1 drug, recent advances in cancer therapy targeting the programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) or its ligand 1 (PD-L1) currently present a challenge to pathologists in that access to 4 different PD-L1 antibodies performed on different immunohistochemistry platforms may be needed to screen potential patients for treatment with an anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agent. Unless harmonization is achieved across classes of targeted therapies, this need for multiple platforms may result in many tests being sent to external laboratories, resulting in delays in testing. A collaborative, multidisciplinary approach incorporating oncologists, pathologists, patient advocacy groups, and regulatory agencies will be needed to develop feasible approaches to developing robust, timely assays for predictive markers for eligibility for specific treatments,21 and the results from the blueprint project between the American Association for Cancer Research, the FDA, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology on feasibility of harmonization for different PD-L1 testing approaches are eagerly awaited.22 Regardless of the regulatory path forward, a close partnership between oncologists and pathologists will be needed to ensure that tumor testing is timely, relevant for medical decision-making, and validated for the targeted therapy under consideration.

Feasibility of Testing and Specimen Selection

Pathologists are excellent resources for the treating physician regarding adequacy and feasibility of testing on specific samples. For instance, tumor cellularity, necrosis, and specimen size, among other factors, all impact the likelihood of success in molecular testing. Pathologists may also offer advice on which sample is preferred when there are multiple different specimens (primary tumor, metastasis, preneoadjuvant or postneoadjuvant therapy) for a particular cancer, taking into account specimen adequacy and tumor heterogeneity.

Biobanking and Research

Pathologists play a central role in the collection of tissues for banking for research purposes and potentially for patient care. In many hospitals with research biobanking programs, remnant tissue from resection specimens is harvested under the supervision of surgical pathologists. Involvement of the pathologist serves to ensure that patient care is not compromised by injudicious selection of tissue needed for diagnosis, staging, or additional clinically indicated tests. Tissue for research is often held in the biobank until the surgical pathology report is finalized and it is clear that the tissue selected for research is not needed for clinical care. Similarly, laboratories have safeguards to ensure that archival paraffin blocks are appropriately retained for clinical care, should additional testing be needed. Beyond involvement for patient care purposes, pathologists are valued collaborators in cancer research using human tissues, as they are the best positioned to identify suitable cases from the archives, select appropriate tissue blocks with adequate amounts of viable tumor, assess quality of the tissue, and evaluate for histopathologic features of particular importance to the research.

Clinical Trial Eligibility

Given the explosive growth in the number of clinical trials evaluating targeted therapies, assessment of particular tumor and genomic characteristics and specific biomarkers has become important in determining clinical trial eligibility. Such testing may be done in local laboratories or in centralized facilities, depending on the marker and the trial design. Pathologists may also provide central pathology review for clinical trials to minimize variability in histopathologic assessment; digital microscopy has simplified this service for some multi-institutional trials and cooperative group studies.23,24

In addition to determination of clinical trial eligibility, pathologic assessment of complete response to neoadjuvant therapy has been adopted as a primary end point in some breast cancer treatment trials,25 again highlighting the importance of pathology assessment in clinical research. Pathologists may also be involved in stratification based on tumor type, grade, stage, and expression of specific biomarkers.26

Preclinical Drug Testing

Although largely invisible to the oncology community in this role, pathologists have long been involved in tissue-based research in drug development. Examples of their contributions in preclinical testing in oncology include predictive toxicology, assessment of xenografts and animal models, analysis of protein expression, and determination of angiogenesis and microvessel density.27

Quality Assessment for Cancer Programs

In collaboration with surgeons, the pathologist plays an integral role in assessing the overall quality of cancer programs for specific tumor types. For example, in 2008, the Commission on Cancer (CoC) instituted Quality of Cancer Care Measures specifying that at least 12 regional lymph nodes should be removed and pathologically examined for resected colon cancer. Because the number of lymph nodes retrieved from colon cancer resection specimens may reflect quality of the surgical resection or of pathologic examination, or both, plus characteristics of the patient and the tumor, this measurement was intended to be used at the hospital or systems level and was not intended for application to individual physician performance.28 Such measures provide valuable benchmarks for cancer programs for comparison with similar programs. Of 23 CoC quality measures, 6 rely on pathologic assessment of the resection specimen, highlighting the important role of pathologists in overall quality of the cancer program.

In summary, the pathologist is ideally positioned to intersect the cancer care continuum at multiple points, from drug development and clinical trials to diagnosis, advanced molecular testing, and participation in quality measures. The role of pathologists on a modern multidisciplinary care team has extended beyond participation in local tumor boards and now impacts most phases of care of the cancer patient. A close partnership between pathologists, oncologists, and members of the multidisciplinary team will continue to play an important role in enhancing cancer care.

References

- Srigley JR. The pathologist as diagnostic oncologist. Pathology. 2009;41:513-514.

- Robboy SJ, Weintraub S, Horvath AE, et al. Pathologist workforce in the United States: I. Development of a predictive model to examine factors influencing supply. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1723-1732.

- Colgan TJ, Geldenhuys L. The practice of pathology in Canada: decreasing pathologist supply and uncertain outcomes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:90-94.

- Henderson-Jackson EB, Bui MM. Molecular pathology of soft-tissue neoplasms and its role in clinical practice. Cancer Control. 2015;22:186-192.

- Gress DM, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al. Principles of Cancer Staging. In: Amin MB, Edge S, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer; 2016:3-30.

- Amin MB, Edge S, Greene FL, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer; 2016.

- Adsay NV, Bagci P, Tajiri T, et al. Pathologic staging of pancreatic, ampullary, biliary, and gallbladder cancers: pitfalls and practical limitations of the current AJCC/UICC TNM staging system and opportunities for improvement. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2012;29:127-141.

- Kostaras X, Shea-Budgell MA, Malcolm E, et al. Is there a role for clinical practice guidelines in multidisciplinary tumor board meetings? A descriptive study of knowledge transfer between research and practice. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27:42-45.

- Lamb BW, Green JS, Benn J, et al. Improving decision making in multidisciplinary tumor boards: prospective longitudinal evaluation of a multicomponent intervention for 1,421 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:412-420.

- Tafe LJ, Gorlov IP, de Abreu FB, et al. Implementation of a molecular tumor board: the impact on treatment decisions for 35 patients evaluated at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. Oncologist. 2015;20:1011-1018.

- El Saghir NS, Keating NL, Carlson RW, et al. Tumor boards: optimizing the structure and improving efficiency of multidisciplinary management of patients with cancer worldwide. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014:e461-e466.

- Ross JS. Clinical implementation of KRAS testing in metastatic colorectal carcinoma: the pathologist’s perspective. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1298-1307.

- The role of the pathologist in diagnosis, quality and patient safety. Hosp Health Netw. 2016;90:38-47.

- Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3997-4013.

- Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer (unabridged version). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:e48-e72.

- Levine RA, Chawla B, Bergeron S, et al. Multidisciplinary management of colorectal cancer enhances access to multimodal therapy and compliance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1531-1538.

- Miller FA, Krueger P, Christensen RJ, et al. Postal survey of physicians and laboratories: practices and perceptions of molecular oncology testing. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:131.

- Sapino A, Roepman P, Linn SC, et al. MammaPrint molecular diagnostics on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16:190-197.

- Goetz L, Bethel K, Topol EJ. Rebooting cancer tissue handling in the sequencing era: toward routine use of frozen tumor tissue. JAMA. 2013;309:37-38.

- Poste G, Carbone DP, Parkinson DR, et al. Leveling the playing field: bringing development of biomarkers and molecular diagnostics up to the standards for drug development. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1515-1523.

- Sholl LM, Aisner DL, Allen TC, et al. Programmed death ligand-1 immunohistochemistry—a new challenge for pathologists: a perspective from members of the Pulmonary Pathology Society. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:341-344.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Public Workshop – Complexities in Personalized Medicine: Harmonizing Companion Diagnostics Across a Class of Targeted Therapies. March 24, 2015. www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/NewsEvents/WorkshopsConferences/ucm436716.htm. 2015. Accessed October 19, 2016.

- Mroz P, Parwani AV, Kulesza P. Central pathology review for phase III clinical trials: the enabling effect of virtual microscopy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:492-495.

- Woodward WA, Sneige N, Winter K, et al. Web based pathology assessment in RTOG 98-04. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:777-780.

- Marchio C, Maletta F, Annaratone L, et al. The perfect pathology report after neoadjuvant therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2015;2015:47-50.

- Nagtegaal ID, West NP, van Krieken JH, et al. Pathology is a necessary and informative tool in oncology clinical trials. J Pathol. 2014;232:185-189.

- Potts SJ. Digital pathology in drug discovery and development: multisite integration. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:935-941.

- American College of Surgeons. Commision on Cancer. CoC Quality of Care Measures. www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb/qualitymeasures. Accessed October 19, 2016.