Personalized medicine has turned a corner, generating attention and excitement in both the general public and the healthcare community. In January 2015, President Barack Obama unveiled a Precision Medicine Initiative in a new effort to revolutionize how we treat disease and improve health, providing funding to support research, development, and innovation for personalized medicine.1,2 The 21st Century Cures Act was passed by the US House of Representatives in July 2015 and provides guidance for the advancement of research and development for personalized medicine.3 Personalized drugs constituted more than 20% of new drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014,4 with 4 new indications approved in July 2015,5 highlighting the growing pace at which personalized medicine products are entering the current market. This change in how we practice medicine, however, may be accompanied by uncertainty and lack of knowledge among patients and healthcare providers (HCPs). Therefore, it is important to provide adequate ongoing education about approaches to personalized medicine.

Personalized medicine has turned a corner, generating attention and excitement in both the general public and the healthcare community. In January 2015, President Barack Obama unveiled a Precision Medicine Initiative in a new effort to revolutionize how we treat disease and improve health, providing funding to support research, development, and innovation for personalized medicine.1,2 The 21st Century Cures Act was passed by the US House of Representatives in July 2015 and provides guidance for the advancement of research and development for personalized medicine.3 Personalized drugs constituted more than 20% of new drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014,4 with 4 new indications approved in July 2015,5 highlighting the growing pace at which personalized medicine products are entering the current market. This change in how we practice medicine, however, may be accompanied by uncertainty and lack of knowledge among patients and healthcare providers (HCPs). Therefore, it is important to provide adequate ongoing education about approaches to personalized medicine.

Personalized medicine is an emerging standard signifying a major shift in the way medicine is practiced, altering how diseases are identified and managed, and changing the way we treat patients and address their associated risk factors. It uses diagnostic tools to identify specific biologic markers, often genetic, that help determine which treatments and procedures will be best for each patient. By combining this information with a patient’s medical records and circumstances (eg, occupations, family relationships, health insurance), personalized medicine allows doctors and patients to develop targeted prevention and treatment plans.

Personalized medicine is an emerging standard signifying a major shift in the way medicine is practiced, altering how diseases are identified and managed, and changing the way we treat patients and address their associated risk factors. It uses diagnostic tools to identify specific biologic markers, often genetic, that help determine which treatments and procedures will be best for each patient. By combining this information with a patient’s medical records and circumstances (eg, occupations, family relationships, health insurance), personalized medicine allows doctors and patients to develop targeted prevention and treatment plans.

In oncology, personalized medicine has enabled the genetic/molecular characterization of certain cancers, such as hematologic malignancies, non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and breast cancer, which has aided in the development of targeted therapies and tailoring of treatment/management strategies.6-8 Indeed, >70% of oncology drugs in development are associated with specific biomarkers (targeted therapies).9 Additionally, >40% and 75% of personalized medicines approved by the FDA in 2014 and 2015, respectively, were for noncancer indications,4,5 suggesting that personalized medicine likely will be the mainstay in most oncology care moving forward, with access to these approaches increasing for a broad range of therapeutic areas.

Personalized medicine impacts multiple stakeholder groups, including consumers/patients, HCPs, and patient advocates. Successful implementation of personalized medicine is influenced by the perspectives of these groups, and effectively and accurately communicating the benefit of personalized medicine to them is therefore important. It is crucial to identify and understand the type and level of familiarity with personalized medicine among different stakeholders; this will increase both awareness and knowledge of this complex area of medicine. Limited research has been published regarding patient preferences and concerns related to treatment choice, outcomes, and cost of healthcare associated with personalized medicine. Additionally, HCPs face challenges in implementing new personalized diagnostic and treatment options; hence, appropriate patient care processes must be established for these new approaches to be successfully integrated into the healthcare system. This highlights the need for greater insight into consumer and provider perspectives of the application of personalized medicine within oncology and the associated hurdles to its implementation into routine clinical practice.

To address this issue, research was conducted with US-based consumers, patient advocacy groups, and HCPs during 2013 and 2014. Here we review and summarize this research to provide decision makers with a multistakeholder point of view on knowledge, attitudes, and awareness of personalized medicine, collectively providing the largest combined data set to date identifying perspectives about personalized medicine in oncology and beyond and the hurdles that will have to be addressed to ensure continued progress in the field.

Methods

Patients, patient advocates, and HCPs participated in multiple focus groups and surveys. The methodologic details of each study are summarized in the Table. Findings from each were reviewed to identify consistent themes that are important for policy and decision makers and to identify areas for potential improvement to increase access and enhance the ability of patients to navigate the healthcare system.

Consumer Perspectives

Consumer research was conducted using focus groups and surveys (Table). Qualitative interviews of participants in 6 focus groups were held across 3 locations in the United States (Washington, DC; Chicago; Dallas) between February 12 and 19, 2013. These focus groups comprised opinion-leading, news-attentive consumers (27 self-identified Democrats and 25 self-identified Republicans, aged 30-64 years) who regularly discussed politics and current events. The purpose of these focus groups was to identify approaches for effectively communicating the value of innovation in personalized medicine within the context of national conversations about deficit reduction and cost containment (unpublished data, 2013; see also www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Userfiles/PMC-Corporate/file/Focus_Group_Results_2013.pdf). A US-based consumer survey was then developed based on the qualitative findings of the Personalized Medicine Coalition (PMC) public opinion focus groups to gauge consumer awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about personalized medicine in general (Table). This telephone survey was administered to 1024 educated, well-informed, financially stable, American adults between March 5 and 16, 2014. The margin of error for the total sample was ±3%. Data collected from this survey were analyzed using descriptive statistics (unpublished data, 2014; see also www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Userfiles/PMC-Corporate/file/us_public_opinion_about_personalized_medicine.pdf).

A second survey10 gauged consumer attitudes and behaviors related to personalized medicine approaches, focusing on the specific application of personalized medicine in oncology. The 14-minute validated, online, quantitative survey was deployed between February 26 and March 4, 2013, to 602 American adults aged ≥30 years (Table). Consumer participants were drawn from GfK’s KnowledgePanel (a probability-based representative online panel). Survey questions covered topics regarding consumer perspectives on their familiarity with personalized medicine, perceived likely adherence to personalized medicine recommendations, perceived economic impact, and personalized medicine testing. Survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and enumeration of responses as proportions and percentages.10

US Health Advocate and HCP Perspectives

A qualitative survey was conducted with oncology patient advocacy group representatives between November 2013 and January 2014 (Table). The anonymous online survey, comprising 14 multiple-choice questions, was translated into 5 languages, pretested with 10 oncology patient groups, and administered to 500 oncology patient groups globally (50% were cancer-only organizations). Thirty-two oncology patient group representatives from North America (25.8% from Canada, 74.2% from United States) responded to the survey. The goals of this survey were to understand oncology patient and patient group perspectives on the current practice and future promise of personalized medicine and to identify areas of evolution for oncology patient groups and challenges to different communities as a result of personalized medicine.

Similarly, a large-scale, global HCP survey was conducted via 1-hour, structured, qualitative telephone interviews with 235 oncology HCPs between February 27 and June 30, 2013, including 40 US oncology HCPs (Table). The survey instrument was pretested and leveraged across markets with minimal market-specific variation. The goal was to assess how an increase in companion diagnostics and personalized medicine (targeted therapies) is expected to impact oncology clinical practice in terms of changes to roles, responsibilities, and collaboration; ability to understand diagnostic information; care of patients; and ability to keep pace with innovation related to cancer care. Survey data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel, and mentions analyses were used to quantify qualitative open-ended responses by grouping them into themes.

Results

Consumer Perspectives in the United States

Findings of Focus Groups with Leading-Edge Consumers

Although the term personalized medicine evoked positive feelings, most informed consumers had low familiarity with and understanding of it. More specifically, only 15% of consumers in the PMC focus groups had heard the term, and just 4% were able to describe the concept accurately. These consumers rarely associated personalized medicine with genetic science or specific types of treatments.

Consumer reactions to 2 accurate, but different, definitions and descriptions of personalized medicine are shown in Figure 1, panel A. Most consumers (80%) had a negative reaction to the US President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology’s definition of personalized medicine.11 Most said they felt tricked and manipulated by the use of technical language that could be difficult to understand; only 15% had a positive reaction to this definition. In contrast, a positive reaction was reported in 78% of consumers after hearing the revised definition of personalized medicine that used a plain-language, consumer-friendly description; only 3% had a negative impression.

When asked about the compelling benefits of personalized medicine, the focus groups revealed that most leading-edge consumers reacted positively to the ability of this information to help patients and physicians make better and more informed treatment decisions, have more control in preventing or treating illness, avoid or reduce side effects, and lead to less trial-and-error medicine. Furthermore, the terms individualized medicine and personalized medicine were most liked by the focus groups to describe the practice area.

Major concerns about personalized medicine identified in these focus groups included fear that it could be used to take away covered choices and that costs would be out of reach for regular people. Eighty-three percent of consumers felt that health insurance companies should cover the cost of personalized medicine tests and treatments, even if that meant a high up-front cost for consumers. Furthermore, consumers expressed a desire to have access to personalized medicine if their doctors said they need it, despite the cost.

General Population Consumer Survey Findings

Respondents to the PMC 2014 consumer survey were generally well-educated, Caucasian, married adults; 52% were women (Table). Similar to the focus group findings among leading-edge consumers, this survey found that consumers in general had low familiarity with or awareness of personalized medicine. More specifically, only 38% had heard of personalized medicine; of those who had heard the term, only 16% felt very informed. Most respondents (69%) expressed interest in learning more about how it works, and 65% reported a positive reaction after hearing a description of it (based on the feedback from the focus groups); only 2% of respondents had negative reactions (Figure 1, panel B).

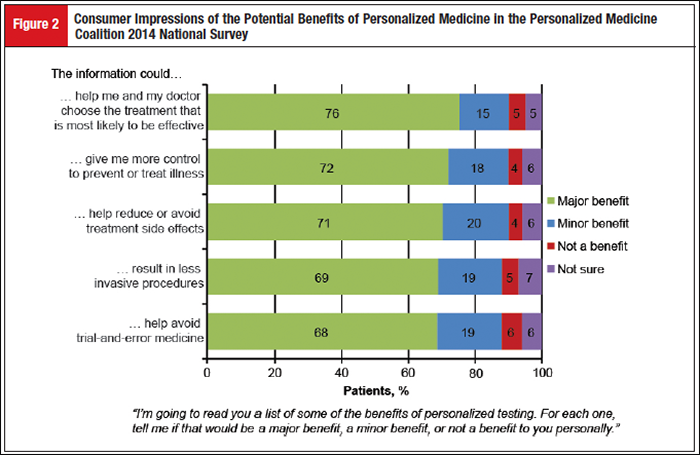

A number of perceived primary benefits were also identified, including the ability of personalized medicine to provide information to help patients and doctors choose the treatment most likely to be effective and to give patients more control in terms of illness prevention and treatment (Figure 2). Data from the survey also identified healthcare access and affordability as the 2 major concerns among consumers. Although consumers recognized the value of personalized medicine, and 63% believed that tests should be covered by insurance, other major concerns were evident, including fear that insurers would not cover it (69%), fear that patients would not be able to afford it (67%), concerns that information could be used to deny coverage for treatment (55%), and worry that personal information could be used against a patient (47%).

Consumer Survey Findings in Oncology

Respondent demographics in the Garfield et al consumer survey10 were similar to those of the PMC 2014 consumer survey (Table). Consumers in the Garfield survey also reported low familiarity with or awareness of personalized medicine. Only 27% had heard of personalized medicine, and 8% of those who had heard of it felt very informed. Most respondents (63%) had a positive reaction after hearing a description of personalized medicine (Figure 1, panel B).

Findings of the Garfield survey indicated that respondents were most interested in learning more about costs associated with testing (45%), their own genetic profiles (41%), the likelihood of response to therapy (36%), and their specific risk for diseases (35%). Tailoring of treatment and prediction of response/harm (44%) or minimizing disease impact (42%) were considered the primary benefits of personalized medicine in oncology. Those with previous diagnoses of potentially fatal cancer were more likely than general respondents to be very interested in testing (68% vs 32%) and more likely to pay out of pocket for testing (62% vs 43%).10 Respondents also showed high willingness to pay for predictive or prognostic tests and high likelihood to seek a second opinion if nonresponder status was implied. Treatment choice was highly driven by out-of-pocket costs; in general, 77% of respondents would choose treatment with a higher likelihood of success and a higher number of side effects, but only 53% would choose such treatment if it was accompanied by high out-of-pocket costs. Finally, 40% and 38% of respondents expected personalized medicine to significantly increase overall healthcare costs in the short term (5 years) and long term (11+ years), respectively.

Oncology Health Advocate Perspectives in North America

The North American health advocate survey builds on data regarding consumer perspectives reported in the other surveys and helps draw a link between the challenges faced by individual oncology patients and those faced by populations of oncology patients. A large proportion of respondents believed they were knowledgeable/very knowledgeable about companion diagnostic tests (67%) and personalized medicine (57%) in oncology. Of the patient organizations surveyed in North America, 53% of respondents believed personalized medicine will have a positive impact on cancer care, and 38% believed it is a completely new approach to the diagnosis, treatment, and management of cancer. Furthermore, 59% agreed that advocacy/patient groups will become more valuable to society as personalized medicine grows. Three key areas for patient support emerged: navigating the healthcare system, ensuring patient access to treatment (costs and patient access to personalized medicine), and providing resources to expand patient knowledge. To improve this level of support, respondents perceived that the activities of patient organizations will have to evolve in response to personalized medicine and diagnostics. This perception was reflected by a systemic need across markets to empower patients and to provide adequate education, funding, and streamlining of care pathways. Although all respondents were excited about the promise of personalized medicine, most identified enduring hurdles for patient advocacy groups, including difficulties navigating the healthcare system to help patients gain access to treatment (78%), lack of accurate information (50%), concerns about maintaining the privacy of patient data (47%), and concerns about adequate support for patients who are not candidates for treatment with personalized medicine (44%). In addition, respondents thought the role for patient advocacy groups would have to change, necessitating that organizations form/strengthen relationships with new stakeholders (61%) and doctors (50%) and create multidisciplinary bodies (59%).

US-Based HCP Perspectives in Oncology

The US-based HCP survey was conducted to provide insight into HCP perspectives and identify potential areas of change to help implement personalized medicine in oncology clinical practice. A number of common themes were identified in this survey. First, HCPs believed there is sufficient guidance for the integration of personalized medicine into clinical practice; more than 50% believed personalized medicine in oncology, including companion diagnostics, will increase in value in the future. Most respondents (>80%) expected that treatment complexity will increase in the short term (3-4 years), and >90% noted that this complexity could be lessened through enhanced educational materials and more defined testing utility. Most (82%) believed guidelines will continue to keep pace with development. Second, US-based HCPs generally agreed that the successful implementation of personalized medicine will require effective communication and collaboration among oncology care professionals, along with an increased capacity within healthcare systems to provide education, training, and clinical support. Although most HCPs are greatly interested in learning about personalized medicine, costs, conflicting obligations, and inadequate materials may limit effective communication and information sharing. There was consensus that HCPs have the technical capabilities to handle personalized medicine, but it was thought that an increase in new treatments and diagnostic tests will give rise to challenges in terms of costs, personnel issues (eg, capacity and capabilities of staff), and increases in data. In particular, an information technology infrastructure is needed to further develop bioinformatics so that data generated from personalized medicine can be stored and processed. Finally, HCPs agreed that the healthcare system infrastructure must change to support adoption of personalized medicine; reimbursement was identified as a key challenge to the implementation of personalized medicine today.

Discussion

This paper reviews and summarizes data on personalized medicine from US-based consumer focus groups and surveys of healthcare consumers, patient advocates, and HCPs. Although these studies were conducted independently, a number of consistent themes were identified that will be of value to policy makers and decision makers. In general, US consumers lacked understanding/awareness of personalized medicine but were optimistic about it when a definition was provided. They wanted to learn more about the costs related to testing, genetic profiling, and the likelihood of response to therapy. Additionally, the HCP and patient advocate surveys suggested that themes emerging consistently among US consumers are also prevalent among other stakeholders. Although the personalized medicine landscape in the United States continues to advance at an encouraging rate, the overall findings presented in this paper highlight the need for increased education and awareness about personalized medicine across the various stakeholder groups.

The overall lack of familiarity with and understanding about personalized medicine among US consumers are in line with findings of previous research. One study demonstrates that patients with breast cancer valued gene expression profiling (a form of personalized medicine testing) but had varying understanding of the test.12 Other studies report different levels of awareness regarding the role of genetics in treatment selection13 and difficulty in understanding basic genetic concepts and genomic risk information among patients receiving genetic counseling associated with personalized medicine.14 Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of patient education about approaches to personalized medicine. Given that accurate, but dissimilar, descriptions of personalized medicine can evoke vastly different consumer reactions, it is important that a nontechnical, consumer-friendly definition of personalized medicine and precision oncology be used to highlight that both individualized care (cancer is driven by different mutations/genomic abnormalities, and selective therapy targeting a patient’s specific mutation would be beneficial15) and proactive care (more information means better control over your health, less trial and error, and faster solutions for better outcomes with fewer side effects15) are important aspects of this approach.

The most compelling perceived benefits of personalized medicine among all types of US consumers included information to help patients and doctors make better treatment decisions and more control in the prevention and/or treatment of illness, suggesting that patients desire to be involved in their treatment choices. However, consumers expressed major concerns about the affordability of personalized medicine. These concerns are valid and in line with previous reports, which note the continually rising cost of insurance premiums15,16 and the high direct medical costs of cancer treatment.17 In the United States, this can often lead to financial hardship for patients and their families, even if they have health insurance. Although personalized medicine may result in increased costs in the near future, successful implementation of personalized treatment strategies can potentially be of great benefit to consumers in the form of improved patient outcomes and long-term reductions in overall healthcare costs.15

Oncology drug-diagnostic combinations enable the stratification of a patient population based on the likelihood of response to, or safety of, a targeted therapy. Two recent examples of FDA-approved companion diagnostics include gefitinib and crizotinib for the treatment of patients with metastatic NSCLC whose tumors have epidermal growth factor receptor and anaplastic lymphoma kinase mutations, respectively.18,19 The ongoing phase 2 National Cancer Institute Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH) trial is also being conducted as part of President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative and will determine whether the use of targeted therapies in patients whose tumors have specific genetic mutations will be efficacious, regardless of their cancer type.20 Therefore, the development of companion diagnostics and the identification of cancer biomarkers are important components of personalized medicine that may improve patient selection and treatment, potentially increasing the likelihood of therapeutic success and improving cost-effectiveness.21-23 Indeed, consumers in the Garfield et al10 survey expressed high willingness to pay for personalized medicine approaches, emphasizing the need for patient access to appropriate diagnostic tests and treatment options. However, the implementation of personalized medicine approaches, such as companion diagnostics, may be hindered by limited and highly variable health insurance reimbursement of these care options.21,23 To facilitate the successful implementation of these new treatment strategies, it is important that their clinical value be accurately assessed for each patient. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Molecular Testing Work Group was assembled in 2011 to identify challenges and provide guidance on molecular tests in oncology and their corresponding usefulness from clinical, scientific, and coverage policy standpoints.24 More recently, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Value in Cancer Care Task Force published the ASCO Value Conceptual Framework, which suggests promoting user-friendly, standardized tools to determine the value of new anticancer therapies compared with established treatments.25

Other surveys of HCPs have reported findings similar to those described here. A small survey of physicians in Canada found that 36% were not familiar with the personalized medicine concept, but 68% thought personalized medicine would be useful once the concept was explained to them.26 As in the HCP study reviewed, professional development—including clinical guidelines and training opportunities for the use of genetic testing and data interpretation—was identified as a key concern of the physicians surveyed.26 In another survey, many internal medicine physicians participating in a personalized medicine trial at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City also demonstrated low familiarity and low comfort interpreting and using genomic information.27 More than 60% of the respondents were unaware of genome-guided prescribing, and 41% were unsure about interpreting pharmacogenetic test results.27 These studies highlight the ongoing need for education on the role of genetic testing in furthering personalized medicine.

The focus group and survey data presented in this paper are associated with potential limitations that should be taken into consideration. The respondents may not be representative of the entire US population; focus groups were limited to well-educated, above-average consumers of news and information from 3 locations within the United States. The patient advocate and HCP surveys were also collected from stakeholders who were generally well informed and motivated to seek information on personalized medicine and new technology. To address these issues, future research will have to be conducted on a larger sample of the general US population, reaching out to local/regional physicians and advocacy groups to gauge their opinions of perceived hurdles to the successful implementation of personalized medicine.

Future research should identify the degree to which participation in clinical trials increases patients’ and providers’ familiarity with the concept of personalized medicine. Furthermore, as the field progresses, challenges to integrating personalized medicine into clinical care should be identified, and best practices designed to address them should be articulated and implemented by healthcare systems.

KEY POINTS

- Personalized medicine is an emerging standard in the United States, as evidenced by the recent unveiling of the Precision Medicine Initiative and the increasing pace at which new personalized medicines are being developed and approved, particularly in oncology

- This paper summarizes the largest combined data set to date identifying perspectives about personalized medicine in oncology and beyond and the hurdles that will have to be addressed to ensure continued progress in the field

- Data on various aspects of personalized medicine, gathered from independent studies of US-based consumer focus groups and from surveys of healthcare consumers, patient advocates, and healthcare practitioners, were reviewed to provide decision makers with a multistakeholder point of view on knowledge, attitudes, and awareness about personalized medicine

- General themes that emerged included lack of understanding and awareness of personalized medicine, concern about access to and cost of personalized medicine, and concern about the necessary information technology infrastructure and the lack of collaboration among key stakeholders

- Successful implementation of personalized medicine in the oncology setting will require increased education and awareness for all stakeholders, improved infrastructure, and greater collaboration among healthcare professionals and across healthcare systems

Conclusion

Personalized medicine is an emerging standard in the United States, as evidenced by the recent unveiling of the Precision Medicine Initiative and the increasing pace at which new personalized medicines are being developed and approved, particularly in the oncology setting; >70% of oncology drugs in development are personalized medicines. Although this continual expansion will be of great value to the healthcare community, the concept of personalized medicine often remains unfamiliar to those who will ultimately use these novel treatment approaches, such as patients and HCPs. The positive aspects should be emphasized to highlight the great promise of personalized medicine to healthcare payers and other stakeholders. The research discussed in this paper identifies areas of unmet need for the successful implementation of personalized medicine in oncology, including increased education/awareness, improved infrastructure, and greater collaboration between care professionals and across healthcare systems. Addressing these needs can lead to vast improvements in quality of care and greater cost savings. Educational programs and policy changes that encourage the development of novel concepts for personalized medicine are needed, thus supporting the continual growth and evolution of this innovative field of medicine. Although preliminary gains are already evident, particularly with regard to FDA approval, progress is still needed to fully leverage the promise of the multitude of targeted therapies and companion diagnostics in development as we strive to advance personalized medicine from promise to routine clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Edward Abrahams, PhD, from the Personalized Medicine Coalition for his intellectual contributions to the PMC studies and reports. Editorial assistance was provided by Maxwell Chang and Traci Stuve of ApotheCom (Yardley, PA). This assistance was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Financial Disclosures

Amy M. Miller has nothing to disclose.

Susan Garfield is an employee of GfK, and a paid consultant to many pharmaceutical companies, but has not received any compensation related to the publication of this article or in the development of its content.

Richard C. Woodman is an employee and stockholder of Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the conception/design and data analysis/interpretation for studies performed at their respective companies. All authors participated in drafting or revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved the final version to be published.

References

- The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. FACT SHEET: President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative. www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/01/30/fact-sheet-president-obama-s-precision-medicine-initiative. January 30, 2015. Accessed January 26, 2016.

- Abrahams E. President Obama’s bet on personalized medicine. Personalized Medicine in Oncology. 2015;4:122-123.

- Committee on Energy & Commerce. The 21st Century Cures Act (HR 6): Help and Hope for Patients Through Biomedical Innovation. http://energycommerce.house.gov/sites/republicans.energycommerce.house.gov/files/114/Cures2015FACT SHEET.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2016.

- Personalized Medicine Coalition. More than 20 percent of the novel new drugs approved by FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research in 2014 are personalized medicines. www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Userfiles/PMC-Corporate/file/fda-approvals-personalized-medicine-2014_adjusted.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2016.

- Miller AM. Turning a corner: how this month’s decisions at FDA inform the debate on drug costs. Personalized Medicine Coalition website. https://personalized medicinecoalition.wordpress.com/2015/07/30/turning-a-corner-how-this-months-decisions-at-fda-inform-the-debate-on-drug-costs/. Updated July 30, 2015. Accessed January 26, 2016.

- Badalian-Very G. Personalized medicine in hematology—A landmark from bench to bed. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2014;10:70-77.

- Hensing T, Chawla A, Batra R, et al. A personalized treatment for lung cancer: molecular pathways, targeted therapies, and genomic characterization. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;799:85-117.

- Sabatier R, Gonçalves A, Bertucci F. Personalized medicine: present and future of breast cancer management. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2014;91:223-233.

- Personalized Medicine Coalition. Biopharmaceutical companies’ personalized medicine research yields innovative treatments for patients. www.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/pmc-tufts-backgrounder.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2016.

- Garfield S, Douglas MP, MacDonald KV, et al. Consumer familiarity, perspectives and expected value of personalized medicine with a focus on applications in oncology. Per Med. 2015;12:13-22.

- President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. Priorities for Personalized Medicine. September 2008. www.whitehouse.gov/files/documents/ostp/PCAST/pcast_report_v2.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2016.

- Bombard Y, Rozmovits L, Trudeau ME, et al. Patients’ perceptions of gene expression profiling in breast cancer treatment decisions. Curr Oncol. 2014;21:e203-e211.

- Goldsmith L, Jackson L, O’Connor A, et al. Direct-to-consumer genomic testing: systematic review of the literature on user perspectives. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:811-816.

- Schmidlen TJ, Wawak L, Kasper R, et al. Personalized genomic results: analysis of informational needs. J Genet Couns. 2014;23:578-587.

- Personalized Medicine Coalition. The Case for Personalized Medicine. 4th ed. Washington, DC; 2014. www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/Userfiles/PMC-Cor porate/file/pmc_the_case_for_personalized_medicine.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2016.

- Claxton G, Rae M, Panchal N, et al. Health benefits in 2013: moderate premium increases in employer-sponsored plans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:1667-1676.

- Elkin EB, Bach PB. Cancer’s next frontier: addressing high and increasing costs. JAMA. 2010;303:1086-1087.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Gefitinib (Iressa). www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm454692.htm. Accessed January 26, 2016.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves Crizotinib. www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm376058.htm. Accessed January 26, 2016.

- National Cancer Institute. NCI-Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH) Trial. www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/nci-supported/nci-match. Updated January 12, 2016. Accessed January 26, 2016.

- Cohen JP, Felix AE. Personalized medicine’s bottleneck: diagnostic test evidence and reimbursement. J Pers Med. 2014;4:163-175.

- Hayes DF. OMICS-based personalized oncology: if it is worth doing, it is worth doing well! BMC Med. 2013;11:221.

- Weldon CB, Trosman JR, Gradishar WJ, et al. Barriers to the use of personalized medicine in breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e24-e31.

- Engstrom PF, Bloom MG, Demetri GD, et al. NCCN molecular testing white paper: effectiveness, efficiency, and reimbursement. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9(suppl 6):S1-S15.

- Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: a conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment options. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2563-2577.

- Najafzadeh M, Davis JC, Joshi P, et al. Barriers for integrating personalized medicine into clinical practice: a qualitative analysis. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:758-763.

- Overby CL, Erwin AL, Abul-Husn NS, et al. Physician attitudes toward adopting genome-guided prescribing through clinical decision support. J Pers Med. 2014;4:35-49.